The Behavior Change Dynamo

Author: Jurgen Appelo

I will (again) run 2,500 kilometers this year. I'm developing a new version of the unFIX model. And I'm writing a novel.

What about you? What are your ambitions?

Do you want to be an excellent programmer? A celebrated artist? Maybe a chef? Do you want to be a high-performing agile team? Perhaps you aspire to something genuinely ambitious and become the first successful agile transformation office in the world?

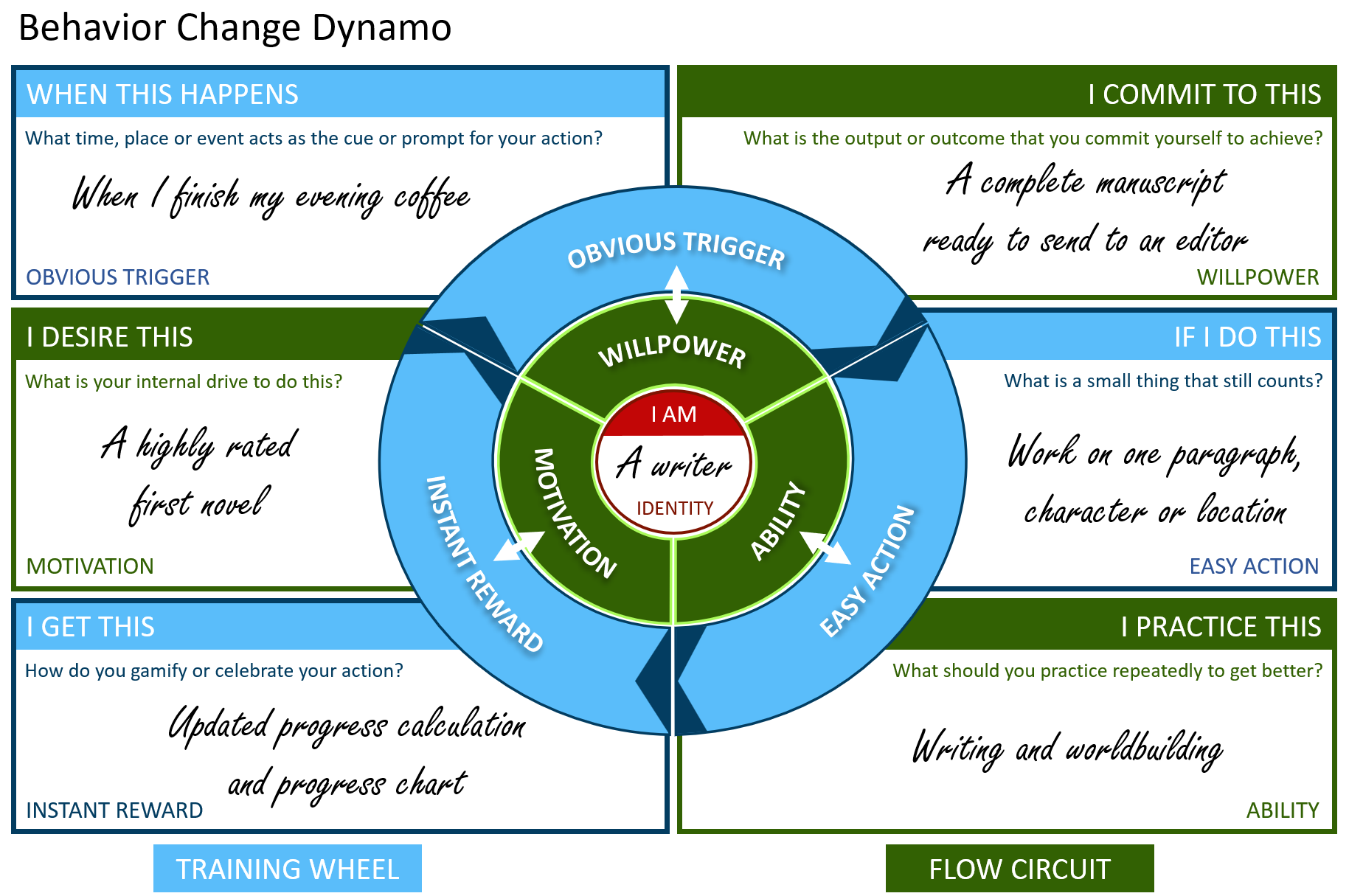

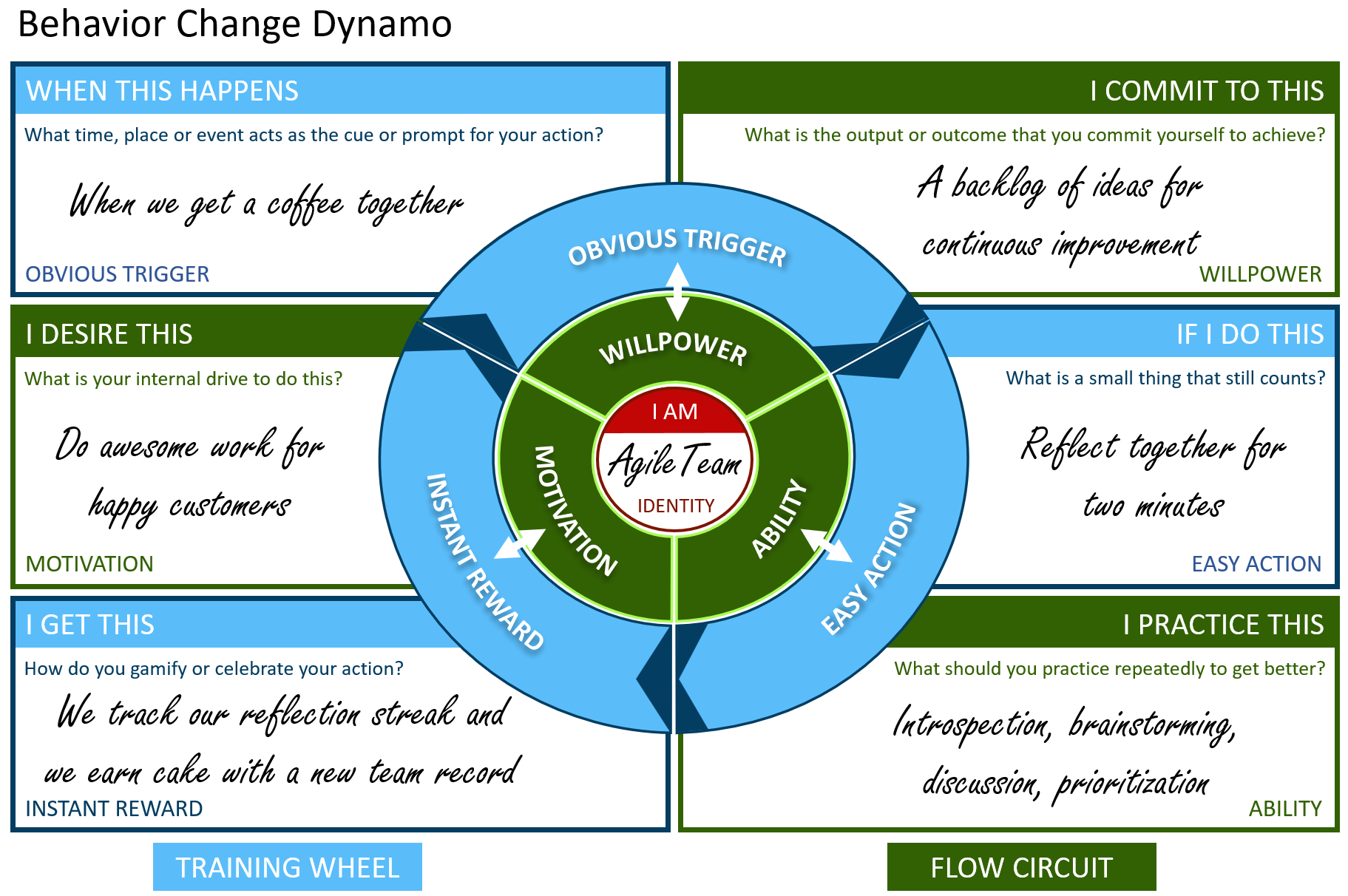

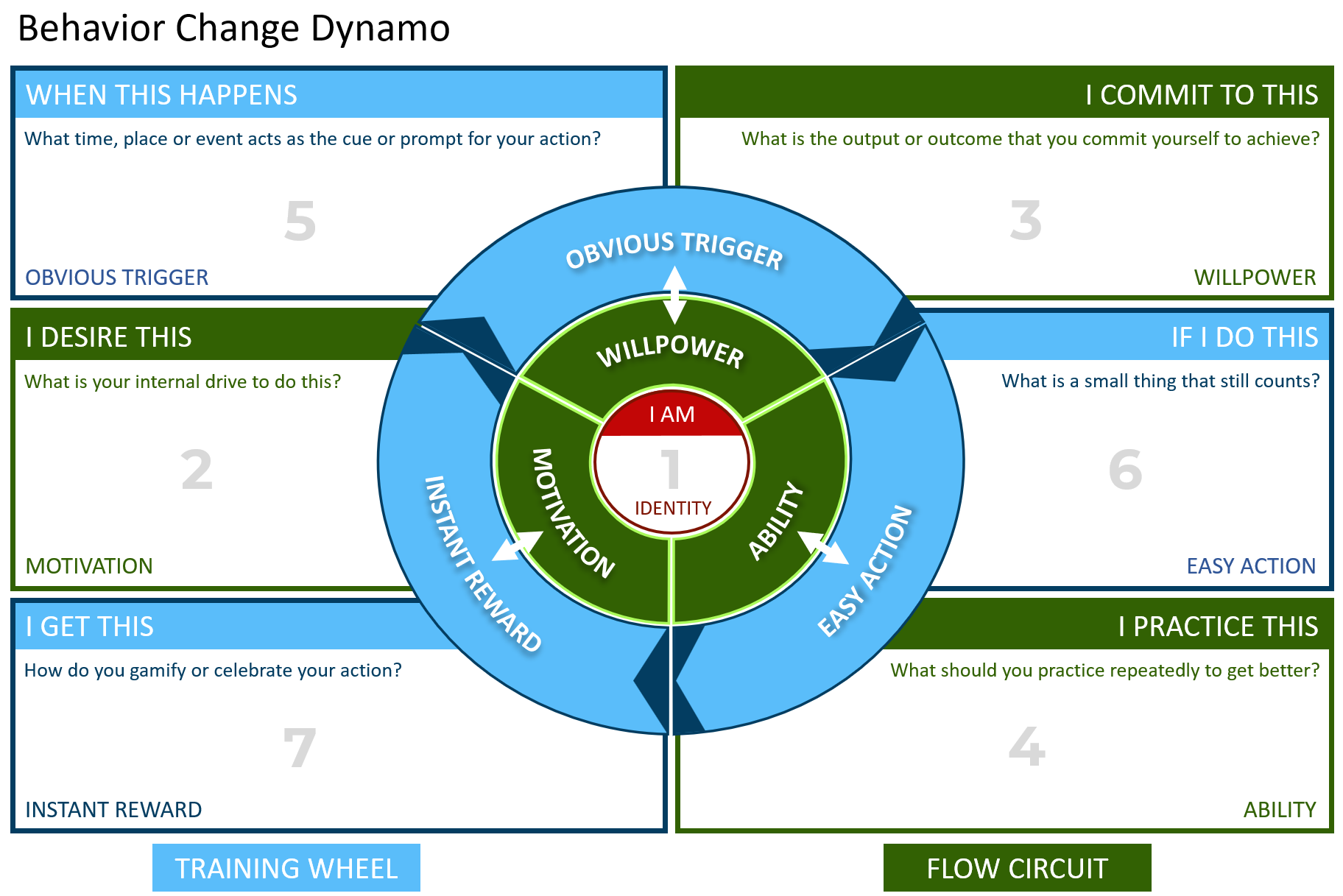

In this article, I explain how you can nurture a growth mindset and increase your willpower, ability, and motivation by wrapping your flow state in a habit loop so that you can achieve impressive results. You can use the Behavior Change Dynamo for personal development, team performance, and customer engagement.

Does this sound like too many buzzwords? No worries! I will show you how it all fits together. In the end, it's just common sense.

Identity

Let's start in the middle. I am a runner. This has not always been the case. For many years, I've been saying, "I hate all sports". I had decided that I was terrible at everything that required physical exercise. I had a significant track record of failed sports engagements. My family has hilarious stories of my feeble attempts at practicing judo, football, and basketball. About eight years ago, I decided that I needed to be more active or end up struggling behind a walker before turning 60.

One of the best self-improvement tips I once read was reframing your identity and casting yourself in a new role. Instead of saying, "I wish I were better at sports," you need to say, "From now on, I am an athlete." Instead of claiming, "I am not creative," you should say, "Starting today, I am a painter." Rather than believing that "you can't cook", you need to commit to the idea of behaving "like a chef".

You can be whoever you want to be, but it starts with adopting a new vision about yourself. Technically, your vision is aspirational, because you're not a celebrated pianist yet. However, you will never become a great pianist if you don't start behaving like a future performer now.

(Note: Smart companies offer a new identity to their customers. Nike's mission statement says, "If you have a body, you are an athlete.")

Step 1. Write who you aspire to be in the middle of the diagram.

Motivation

Most likely, you adopt a new vision about yourself because something motivates you. I am motivated by my desire to feel healthy, even at an old age. (I still want to be able to run a marathon when I'm 80!) Maybe you want to be a great development team because you love the idea of writing world-class software. Perhaps you love the idea of serving your friends and family a fabulous four-course dinner. Or you envision yourself signing your newly published novel in a bookstore.

Daniel Pink's Drive is probably the most famous book that covers intrinsic motivation. I created the Moving Motivators game based on self-determination research and the 16 basic desires of Steven Reiss. And many other authors have made their own contributions to the area of motivation.

The problem is, motivation is often a feeble friend. It is highly context-dependent. Motivation can change with your mood, the weather, your health, and what your lover said to you last night. There have been many days when I wasn't motivated to go running. Orchestras cannot rely on their musicians to always be motivated. Sometimes, a chef just has an awful day. And no matter how much your company invests in employee engagement or customer engagement initiatives, neither you nor your colleagues or clients are motivated every day. But the work still needs to be done!

Step 2. Write down your internal drive and desire in the Motivation section.

Willpower

I once went running around Helsinki in the worst weather I ever experienced. It was cold, rainy, and windy. The gale blew tears from my eyes, and the droplets almost turned into icicles before they left my cheeks. But I was running! This was not motivation but pure willpower (also referred to as zeal, perseverance, or self-discipline). The weather didn't motivate me, but still, I made myself go running.

Angela Duckworth's book Grit offers many stories of people achieving outstanding results because they forced themselves to show up. Olympic athletes don't wait to perform their daily routines and exercises until they feel a desire to do so. And the best-earning performers don't claim that they reached the top by just riding the wave of their intrinsic motivation. As Freddy Mercury sang, "The show must go on. I'll face it with a grin. I'm never giving in. On with the show."

The problem is that willpower is prone to depletion. Relying on grit alone is exhausting. You can train your self-discipline muscle so that your performance can last a good while longer (and top-performers do this), but everyone, at some point, needs to recharge. Even Freddy Mercury needed a break now and then.

Step 3. Add your commitment and planned outcome under Willpower.

Ability

The interesting thing is that neither motivation nor willpower is always needed to get things done and to get (slightly) better at what you do. When you drive the same commute a few thousand times, you will probably become good at going that particular route. You will know all the nooks and crannies, bumps, turns, and potholes. Motivation for this commute plays no role, and neither does willpower. You could almost do it blindly.

Anders Ericsson's book Peak describes how deliberate practice and continuous repetition (with variation and feedback) can turn you into a master of just about anything. Talent is highly overrated. The best chess players become grandmasters because they play a lot of chess. The best football players in the world have probably been practicing since they were kids. And the best-performing software teams become highly skilled because they just write a ton of code.

Even though innate talent and physical attributes can play a (minor) role in specific jobs, the available research suggests that ability grows primarily from the amount of deliberate practice and repetition that people put in. (Of course, if you want to boost your effectiveness, you shouldn't just go through the motions while running on auto-pilot. It helps if growth in ability is complemented with an increase in motivation and willpower.)

Step 4. Under Ability, write down what you should practice deliberately.

The first four steps form the Flow Circuit of the Behavior Change Dynamo:

I AM (identity)

I DESIRE THIS (motivation)

I COMMIT TO THIS (willpower)

I PRACTICE THIS (ability)

Flow and Habits

A steady increase of motivation, willpower and ability is achieved with a flow state (or being in the zone). You grow your skills as a team by doing things just outside your current abilities, which requires a certain amount of motivation and willpower. Without motivation, you have no reason to do it. Without willpower, you have no discipline to do it.

Sadly, most people struggle here (me included). Very few of us have the same level of motivation and willpower that professional athletes and performers have. In fact, these professionals probably also didn't have the same levels at the start of their careers. A state of flow doesn't arrive as if by magic. We need to train ourselves to achieve flow and adopt a habit of self-improvement.

All habit-forming research agrees on the idea that the habit loop consists of three parts. They go by different names, but they always mean the same thing: trigger-action-reward (or prompt-behavior-celebration or stimulus-response-consequence). And in Nir Eyal's book Hooked, we can read that this not only applies to ourselves but also to our customers.

Obvious Trigger

Willpower is the internal push to do something. If your willpower is not strong enough, it helps to have an external trigger to get you going. I start running after I wake up. I work on my novel after my evening coffee. And I begin a moment of reflection when I get into bed.

The habit-forming literature (such as James Clear's Atomic Habits) suggests that new behaviors are most easily adopted when they begin with an obvious trigger (sometimes called a cue, prompt, or stimulus). When this happens, you do that. It's straightforward. The trigger can be a specific time, a place, or an event, and when you connect habit B to habit A, it is called a habit chain or habit stacking.

Experience shows that it is easiest for people to add new habits between or just after other habits. For example, you could do twenty minutes of refactoring each time after lunch or checking the Slack channels only after a meeting. Alternatively, you can do something at a specific time (when it's 9 am, you answer your emails), in a particular place (when you get a coffee together, you do a mini-retrospective), or with a specific event (after each toilet break, you drink some water).

Training yourself and your team to act out good behaviors while responding to triggers is an easy way to compensate for the absence or depletion of willpower. When you do things habitually and automatically, there's less need to rely on your self-discipline. (There is a marker between Willpower and Obvious Trigger to indicate that this boundary can move: when your willpower shrinks, you need more obvious triggers.)

Step 5. Under Obvious Trigger, add what time, place, or event will act as the cue or prompt.

Easy Action

Your ability to do something depends on your skill and the difficulty of the task. When you're good, you can do a lot. Duh! However, most of us start out not being good at anything we try. In the beginning, I was a terrible runner; I sucked as a writer, and I was embarrassing as a speaker.

That's why the habit books (including BJ Fogg's Tiny Habits) suggest to making your action (sometimes called the behavior, routine, or response) as small as possible. Don't start with a ten-kilometer run! Just begin easy, with a 500-meter walk. The idea is that you first work on making something a habit, and only then (after the practice has successfully lodged in your brain) do you gradually increase the difficulty level. Start small before growing big!

For example, your first retrospectives should be two minutes, not two hours. It's totally fine if your first cooking experiences are just baked eggs or pancakes. Your initial refactoring attempts might involve just one or two lines of code. And the first level of every game is always ridiculously easy. First, you build the habit; then, you make it harder.

Later, when you've repeatedly and successfully gone through the habit cycle, you steadily build up your ability and start raising the bar for yourself. (Again, there is a marker between Ability and Easy Action to indicate that this boundary is moveable: when your ability grows, you can do actions that are harder--or less easy.)

Step 6. Under Easy Action, write down which small behavior still counts as deliberate practice.

Instant Reward

New habits won't stick if there is no immediate reward (sometimes referred to as consequence, satisfaction, or celebration). The reward can be a sense of immediate relief, like the first time when I ordered an Uber car and instantly loved the fact that I didn't have to search for a taxi, that I didn't need any cash, and that nobody was ripping me off. Other times, the reward offers instant pleasure, such as the first time I used YouTube Music and immediately found some almost-forgotten songs that Spotify didn't have.

The instant reward is where gamification comes in. Books such as Jane McGonigal's Reality is Broken offer examples of habits people and teams can develop by gamifying their good behaviors. I made significant progress as a runner by celebrating my runs with chocolates, aiming for longer streaks (my record is five months of day-to-day running), and checking out my daily progress toward my target (2,500 kilometers this year).

I should emphasize that the gamification of good behaviors with short-term rewards is only a trick that you use to compensate for your unreliable long-term motivation. It would be great if my motivation to be a healthy person would get me out of bed every morning. Sadly, that is not the case. Most often, it is the promise of short-term rewards that helps me get up. The long-term motivation of feeling healthy is not the first thing I think about when waking up at 5:30 am. (There is a marker between Motivation and Instant Reward to show that this boundary can move as well: when your long-term motivation grows, you may care less about the instant rewards.)

Step 7. Under Instant Reward, add how you will gamify or celebrate your good behaviors.

The last three steps form the outer Training Wheel of the Behavior Change Dynamo:

WHEN THIS HAPPENS (obvious trigger)

IF I DO THIS (easy action)

I GET THIS (instant reward)

Training Wheel

It is essential to understand that the habit cycle is supposed to help you grow and improve your performance. The more often you repeat your habits and do the right behaviors, the more you develop your skills and abilities. And with increased capabilities, you should stop relying on easy actions and start raising the bar for yourself. Ultimately, your two-minute retros should become full-blown retrospectives!

Over time, you might also see your motivation becoming more reliable when you start noticing the long-term effects. This means there is less need for you to rely on gamification trickery and instant rewards. Likewise, another side effect of going through the habit cycle often enough is that you may see your willpower strengthening over time. You won't depend on external triggers anymore. You can then say goodbye to your agile coach and your personal trainer because, hopefully, self-discipline has taken over.

That's why I call the outer circle a training wheel. Its purpose is to help you get started and to help you going forward. But what you're really after is increased ability, motivation, and willpower. The purpose of the Behavior Change Dynamo is to wind up your flow circuit.

Flow Circuit

The inner circle is all about growing as a person or as a team. Developing your ability, motivation, and willpower means repeatedly getting into a state of flow or "being in the zone". You perform challenging activities just outside your comfort zone, increasing your skills with deliberate practice, intrinsic motivation, and self-discipline. The concept of flow is famously described in the book Flow by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi.

Some experts criticize relying on habit-forming because the risk is that people do not continuously raise the bar and are reluctant to do things that feel uncomfortable. When they just go through the motions while behaving like on auto-pilot, they cannot expect to increase their performance very much, neither as a person nor as a team. Like in a never-ending commute, they just get stuck in their habit loop, forgetting why it's there in the first place.

For this reason, the Flow Circuit is the central element of the Behavior Change Dynamo. The habit loop wraps around it to indicate that the only purpose of new habits is to feed the flow.

Mindset

Finally, we come back to where we started: in the middle. That's where you wrote down the person you aspire to become or the kind of team you choose to be, or the new self-image you want to offer to your customer.

The growth mindset is a choice. You can become (almost) anyone you want, said Carol Dweck in her book Mindset. But you need to make that decision first and then tell yourself that, from this moment forward, you will behave differently. (Or you help your team to behave differently, or you help your clients to reinvent themselves.)

In the next circle, the flow circuit, you think about what motivates you, where your willpower should take you, and which abilities you need to develop. But it's OK to admit that, like almost everyone else, you are human, and thus you are fallible. That's why you use the outer circle to define one or more habits that will act as a training wheel. You ask yourself, "When will I do which small actions, and how will I reward myself for doing them?"

Once you've picked new habits for yourself, your team, or your customers, it's best to treat these as an experiment. Maybe the selected trigger isn't obvious enough. Perhaps the chosen action is still too hard. Maybe the reward is not satisfying at all. No problem! Just keep tweaking until the training wheel starts to work.

When the habit works and the training wheel is spinning happily, you work your way back inwards. You steadily raise the bar to gain increased ability, motivation, and willpower. And, finally, a new identity.

I am a runner, a model creator, and a novel writer.

What are you?